Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

27 Jan 2024

A single changing hypernetwork to represent (social-)ecological dynamicsCedric Gaucherel, Maximilien Cosme, Camille Nous, Franck Pommereau https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.30.564699The Dawn of Dynamic Hypergraph Modelling in EcologyRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Catherine Matias and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Catherine Matias and 1 anonymous reviewer

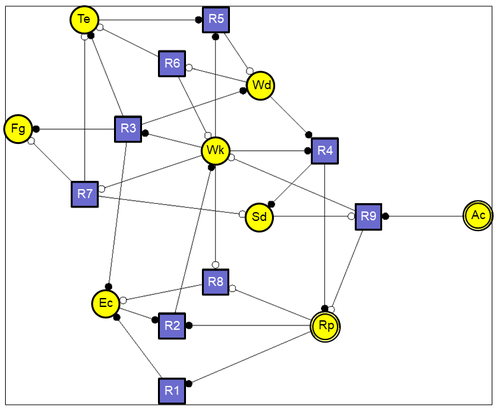

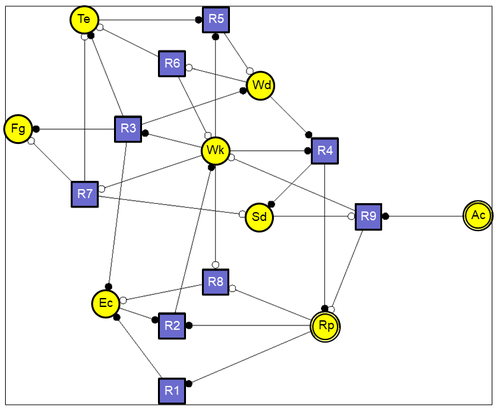

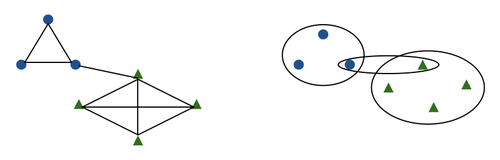

The study of Gaucherel et al. (2024) represents a groundbreaking shift in the field of ecosystem representation and management (DeFries and Nagendra 2017), offering a comprehensive and innovative approach that emphasises the importance of dynamic and complex models to accurately understand and preserve our ecosystems. At the heart of this pioneering work is the introduction of advanced representational methods such as interaction networks and hypergraphs (Bretto 2013; Golubski et al. 2016), which mark a significant departure from traditional static models. These novel representations are adept at capturing the intricate, multi-component interactions within ecosystems, thereby providing a much more nuanced and interconnected view of ecological systems. This approach is particularly innovative as it moves beyond the simplicity of previous models, offering a dynamic, fluid, and interconnected perspective of ecological dynamics that is more reflective of the real-world complexity of these systems. Furthermore, the study proposes the integration of social networks with ecological ones (Sosa et al. 2021; Sueur 2023), acknowledging the profound impact that human activities have on natural systems (Afana 2021; Elmqvist et al. 2021; Pelé et al. 2021). This interdisciplinary approach is pioneering in its attempt to bridge the gap between social and ecological studies, underscoring the interconnectedness of natural and human systems and highlighting the need for a holistic approach to ecosystem management (Stokols et al. 2013; Stone-Jovicich 2015). The significance of the study lies not only in its methodological innovations but also in the implications it holds for the field of ecology and environmental management. By employing these advanced methodologies, the study provides a more thorough understanding of ecosystems. By considering a wide range of components and their interactions, these models offer insights into the complex dynamics of ecosystems, which are crucial for developing effective conservation and management strategies. This comprehensive approach is particularly important in an era where ecosystems are increasingly threatened by a variety of factors, including climate change, habitat destruction, and pollution (Mantyka‐pringle et al. 2012; Trathan et al. 2015). Additionally, the dynamic nature of the proposed models, especially the use of hypergraphs, facilitates the adaptive management of ecosystems. By accurately representing the changing interactions and components within these systems, these models enable managers and policymakers to respond more effectively to ecological changes, ensuring that conservation efforts are both effective and timely (Ascough Ii et al. 2008; Fischer et al. 2009; McKinley et al. 2017). Moreover, the advanced modelling techniques proposed by the study have the potential to significantly improve predictive capabilities regarding ecosystem dynamics. Understanding the complex interactions and the long-term dynamics of ecosystems allows for better anticipation of future changes and challenges, a crucial aspect in a rapidly changing world where ecosystems are under constant threat. In conclusion, this study marks a significant advancement in the field of ecological representation and management. Its innovative approach in utilising complex models like hypergraphs and integrating social and ecological networks provides a more comprehensive, dynamic, and nuanced understanding of ecosystems. Such innovations are crucial in an era of rapid environmental change and increasing anthropogenic pressures. By enhancing our ability to understand, predict, and manage ecosystem dynamics, this study lays the groundwork for more effective conservation strategies and ecosystem management practices. It underscores the need for a holistic approach to understanding and preserving our natural world, recognising the intricate and interconnected nature of ecosystems and the pivotal role humans play within them. References Afana R (2021) Ecocide, Speciesism, Vulnerability: Revisiting Positive Peace in the Anthropocene. In: Standish K, Devere H, Suazo A, Rafferty R (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Peace. Springer, Singapore, pp 1-18 Ascough Ii J, Maier H, Ravalico J, Strudley M (2008) Future research challenges for incorporation of uncertainty in environmental and ecological decision-making. Ecol Model 219:383-399 Bretto A (2013) Hypergraph theory. Introd Math Eng Cham Springer 1: DeFries R, Nagendra H (2017) Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science 356:265-270 Elmqvist T, Andersson E, McPhearson T, et al (2021) Urbanization in and for the Anthropocene. Npj Urban Sustain 1:6 Fischer J, Peterson GD, Gardner TA, et al (2009) Integrating resilience thinking and optimisation for conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 24:549-554 Gaucherel C, Cosme M, Noûs C, Pommereau F (2024) A single changing hypernetwork to represent (social-)ecological dynamics. bioRxiv, 2023.10.30.564699, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. Golubski AJ, Westlund EE, Vandermeer J, Pascual M (2016) Ecological networks over the edge: hypergraph trait-mediated indirect interaction (TMII) structure. Trends Ecol Evol 31:344-354 Mantyka‐pringle CS, Martin TG, Rhodes JR (2012) Interactions between climate and habitat loss effects on biodiversity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Glob Change Biol 18:1239-1252 McKinley DC, Miller-Rushing AJ, Ballard HL, et al (2017) Citizen science can improve conservation science, natural resource management, and environmental protection. Biol Conserv 208:15-28 Pelé M, Georges J-Y, Matsuzawa T, Sueur C (2021) Editorial: Perceptions of Human-Animal Relationships and Their Impacts on Animal Ethics, Law and Research. Front Psychol 11: Sosa S, Jacoby D, Lihoreau M, Sueur C (2021) Animal social networks: Towards an integrative framework embedding social interactions, space and time. Methods Ecol Evol 12:4-9 Stokols D, Lejano RP, Hipp J (2013) Enhancing the Resilience of Human-Environment Systems: a Social Ecological Perspective. Ecol Soc 18: Stone-Jovicich S (2015) Probing the interfaces between the social sciences and social-ecological resilience: insights from integrative and hybrid perspectives in the social sciences. Ecol Soc 20: Sueur C (2023) Socioconnectomics: Connectomics Should Be Extended to Societies to Better Understand Evolutionary Processes. Sci 5:5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci5010005 Trathan PN, García‐Borboroglu P, Boersma D, et al (2015) Pollution, habitat loss, fishing, and climate change as critical threats to penguins. Conserv Biol 29:31-41 | A single changing hypernetwork to represent (social-)ecological dynamics | Cedric Gaucherel, Maximilien Cosme, Camille Nous, Franck Pommereau | <p style="text-align: justify;">To understand and manage (social-)ecological systems, we need an intuitive and rigorous way to represent them. Recent ecological studies propose to represent interaction networks into modular graphs, multiplexes and... |  | Algorithms for Network Analysis, Biological Networks, Community structure in networks, Ecological networks, Geometry and topology of networks or graphs, Network models, Qualitative methods in network analysis, Social networks, Temporal networks | Cédric Sueur | 2023-11-03 17:18:11 | View | |

14 Jun 2021

Behavioural synchronization in a multilevel society of feral horsesTamao Maeda, Cedric Sueur, Satoshi Hirata, Shinya Yamamoto https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.21.432190Feral horses synchronize their collective behavior at multiple levels of organizationRecommended by Brenda McCowan based on reviews by Frédéric Amblard, Krishna Balasubramaniam, Krishna Balasubramaniam and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their article “Behavioural synchronization in a multilevel society of feral horses”, Maeda and colleagues (2021) use stochastic multi-agent based modeling to explore the degree to which feral horses synchronize their behavior across multiple levels of organization. The authors compare a drone-derived empirical data set on a feral population of horses with simulated data from multi-agent-based models to determine whether behavioral synchronization of resting and movement states in a multilevel society can be described by one of three models: A) independent model in which horses do not synchronize, B) anonymous model in which horses synchronize with any individual in any unit, C) unit-level social model in which horses synchronize only within units and D) herd-level social model in which horses synchronize across and within units, but internal synchronization is stronger. In a series of 100 simulations for each of seven different models, the authors conclude that evidence for the herd-level model had the strongest support in relation to the empirical data. This finding suggests that connections among individuals in such multi-level societies are rather complex in that local connections are not the only interactions driving social behavior, and specifically synchronization. This approach could be successfully applied to a number of different species that exhibit multi-level organization and possibly fission-fusion dynamics. This study is especially innovative and interesting for three major reasons. First, the use of drone technology to successfully identify individual animals and generate social networks is highly novel and permits the study of large multi-level social groups of animals that previously have been challenging to study due to limitations in collecting data at an appropriate scale. Second, the comparison of multi-agent-based models with actual empirical data is highly applauded. Most agent-based studies design their parameters from previous empirical studies, (sometimes with questionably simple assumptions) but rarely do they actually compare model outputs to their own empirical data. This is an important next step in the burgeoning field of agent-based modeling. Finally, this study sheds light on the utility of using relatively simple mathematical models to explain highly complex behavior. It also highlights that feral horses can synchronize their behavior beyond clustered local connections which suggests that they possess the cognitive ability to track the behavior of individuals at higher social orders. As the authors state, in a multilevel society, inter-unit distance should be moderate, that is “not too close but not too far” because this strategy simultaneously avoids inter-unit competition while also providing the benefits of social buffering that comes with large group living, such as protection from bachelors or predators. As the authors dutifully note, there were also some limitations to the study: (1) the relatively sparse empirical dataset that made it difficult to resolve the relative fitness of the two herd-level models (absolute versus proportional social models), (2) the lack of a temporal component that would provide a better understanding on how synchronization flows through the social/spatial network, and (3) the limited variation in the parameters tested which constrained identification of their true function in the model. Such limitations, however, provide fruitful avenues for further development of the model in future studies. Overall then, this study provides new insights into the processes underlying the behavioral synchronization process and thus nicely contributes to the understanding of collective behaviors in complex animal societies as well as the evolution and functional significance of multi-level animal societies. This study is a fine addition to both the fields of agent-based modeling and the evolution of collective behavior in complex societies. I thus highly endorse its publication. References Maeda T, Sueur C, Hirata S, Yamamoto S (2021) Behavioural synchronization in a multilevel society of feral horses. bioRxiv, 2021.02.21.432190, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Network Science. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.21.432190 | Behavioural synchronization in a multilevel society of feral horses | Tamao Maeda, Cedric Sueur, Satoshi Hirata, Shinya Yamamoto | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioural synchrony among individuals is essential for group-living organisms. It is still largely unknown how synchronization functions in a multilevel society, which is a nested assemblage of multiple social lev... |  | Animal networks, Biological Networks, Dynamics on networks, Network models, Social networks, Synchronization in networks | Brenda McCowan | Krishna Balasubramaniam, Brianne Beisner, Frédéric Amblard | 2021-02-23 02:46:18 | View |

08 Mar 2024

Comparison of modularity-based approaches for nodes clustering in hypergraphsVeronica Poda, Catherine Matias https://hal.science/hal-04414337v2A theoretical and empirical evaluation of modularities for hypergraphsRecommended by Remy Cazabet based on reviews by salvatore citraro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by salvatore citraro and 1 anonymous reviewer

Hypergraphs, as a framework to model higher-order interactions, have attracted a lot of attention in recent years. One particularly fruitful research direction consists of transposing well-defined notions in simple graphs to this new paradigm. A difficulty, but also an interesting opportunity, of this task is that a single concept in simple graphs might correspond to multiple ones in the domain to which it is transposed. The problem has for instance been discussed for link streams in Latapy et al. (2018), for notions as simple as node neighborhoods or the notion of shortest path. In the present article (Poda and Matias 2024), Poda and Matias focus on the concept of modularity and, indeed, they identify multiple definitions of modularity for hypergraphs in the literature (Chodrow et al., 2021, Kaminski et al., 2021). The first interesting contribution is the unification of these different representations using a common framework. They can thus compare, based solely on the definitions themselves, theoretical similarities and differences between those modularities for hypergraphs. In the second part of their contribution, they turn towards the empirical evaluation of these methods. Community detection has a long tradition of experimental articles, comparing on selected benchmarks the strengths and weaknesses of selected methods, from the seminal work from Lancichinetti and Fortunato (Lancichinetti et al., 2009), to recent works comparing, for instance, modularity methods in dynamic graphs (Cazabet et al., 2020). The authors thus point to existing implementations and start comparing them using existing benchmarks for hypergraphs (Brusa and Matias, 2022, Kaminski et al., 2023). This confrontation between theoretical definition and actual networks with varying properties allows them to identify methods that do not perform as expected. Furthermore, they do not solely focus on classification performance but also evaluate other factors such as scalability. Their findings reveal that all methods perform poorly in this aspect. These observations pave the way for future work. To conclude, this work is a very relevant contribution to the field. One could say that the first empirical comparison of methods in a particular field is a sign that it has become mature, and that is maybe one of the conclusions to draw from this article. References Poda, V., & Matias, C. (2024). Comparison of modularity-based approaches for nodes clustering in hypergraphs. arXiv preprint. HAL, https://hal.science/hal-04414337v2 | Comparison of modularity-based approaches for nodes clustering in hypergraphs | Veronica Poda, Catherine Matias | <p>Statistical analysis and node clustering in hypergraphs constitute an emerging topic suffering from a lack of standardization. In contrast to the case of graphs, the concept of nodes' community in hypergraphs is not unique and encompasses vario... |  | Clustering in networks, Graph algorithms | Remy Cazabet | 2024-01-25 10:19:55 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Differential effects of multiplex and uniplex affiliative relationships on biomarkers of inflammationJessica Vandeleest, Lauren J. Wooddell, Amy C. Nathman, Brianne A. Beisner, Brenda McCowan https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514247Multiplex vs. Uniplex: Deciphering the Differential Health Impacts of Complex Social Interactions in Rhesus MacaquesRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Tamao Maeda and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Tamao Maeda and 2 anonymous reviewers

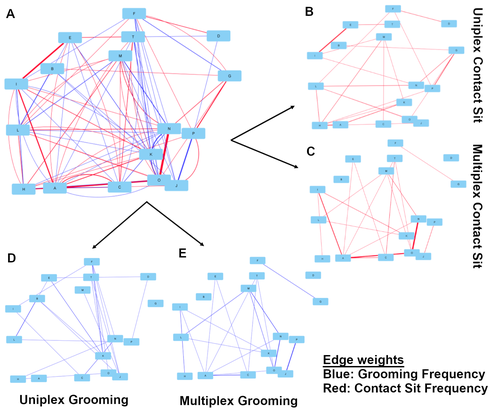

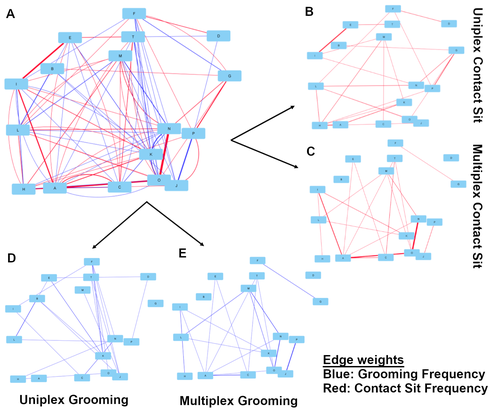

Social relationships are recognized as an important age-related mediator of health in humans and fitness-related traits in animals (Sueur et al., 2021). Vandeleest et al. (2024) is a pioneering exploration into the complex interplay between social relationships and health in rhesus macaques. It breaks new ground by differentiating between two types of affiliative relationships – multiplex (engaging in multiple types of affiliative behaviors like grooming and contact sitting) and uniplex (involving only one type of behavior, such as grooming) (Beisner et al., 2020). The study's crux lies in its novel approach to understanding how these differing social interactions correlate with biomarkers of inflammation, namely pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-alpha. The research is innovative in its use of social network analysis (Sosa et al., 2021), allowing for a nuanced view of the rhesus macaques' social dynamics. It reveals that multiplex grooming networks, characterized by more modular structures and kin bias, are associated with lower inflammation levels. This is in contrast to uniplex grooming networks, where a stronger link to social status correlates with higher inflammation. These findings suggest that multiplex relationships could serve as supportive, health-promoting bonds, while uniplex relationships might be more transactional, with possible physiological costs. Moreover, the study's results highlight the importance of the diversity of affiliative interactions within a dyad. It posits that relationships involving multiple types of affiliative behaviors may have different implications for health and well-being compared to those based on a single behavior type, even if interaction rates are similar. This insight opens up new avenues for understanding the health implications of social behaviors in non-human primates and potentially in humans (Sueur et al., 2021). Furthermore, the paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the network structures, examining kin bias, clustering, modularity, and associations with dominance rank. It also evaluates the correlations between individual network positions and health markers, offering a multifaceted understanding of how social networks influence physical well-being. In essence, this research makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the link between sociality and health. It underscores the complexity of social relationships (Moscovice et al., 2020) and their varied impacts on health, suggesting that the nature of social bonds (multiplex vs. uniplex) plays a critical role in determining their health consequences. This study not only enhances our comprehension of primate social behavior but also has broader implications for the fields of social neuroscience, behavioral ecology, and health psychology. References Beisner, B., Braun, N., Pósfai, M., Vandeleest, J., D’Souza, R., & McCowan, B. (2020). A multiplex centrality metric for complex social networks: Sex, social status, and family structure predict multiplex centrality in rhesus macaques. PeerJ, 8, e8712. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8712 Moscovice, L. R., Sueur, C., & Aureli, F. (2020). How socio-ecological factors influence the differentiation of social relationships: An integrated conceptual framework. Biology Letters, 16(9), 20200384. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0384 Sosa, S., Sueur, C., & Puga-Gonzalez, I. (2021). Network measures in animal social network analysis: Their strengths, limits, interpretations and uses. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 12(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13366 Sueur, C., Quque, M., Naud, A., Bergouignan, A., & Criscuolo, F. (2021). Social capital: An independent dimension of healthy ageing. Peer Community Journal, 1. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.33 Vandeleest, J. J., Wooddell, L. J., Nathman, A. C., Beisner, B. A., & McCowan, B. (2024). Differential effects of multiplex and uniplex affiliative relationships on biomarkers of inflammation. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.01.514247 | Differential effects of multiplex and uniplex affiliative relationships on biomarkers of inflammation | Jessica Vandeleest, Lauren J. Wooddell, Amy C. Nathman, Brianne A. Beisner, Brenda McCowan | <p>Social relationships profoundly impact health in social species. Much of what we know regarding the impact of affiliative social relationships on health in nonhuman primates (NHPs) has focused on the structure of connections or the qualit... |  | Animal networks, Multilayer, multiplex or multilevel Networks | Cédric Sueur | 2022-11-08 00:25:10 | View | |

29 Aug 2021

Improving human collective decision-making through animal and artificial intelligenceCédric Sueur, Christophe Bousquet, Romain Espinosa and Jean-Louis Deneubourg https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03299087Bio-inspired solutions for collective decision-making in a networked societyRecommended by Frédéric Amblard based on reviews by Camelia Florela Voinea and 1 anonymous reviewerFormal voting biases and weaknesses like Arrow's or Condorcet's paradoxes are known for quite a long time, but they are often considered as curiosities for mathematicians and cases that rarely occur in practice. Although, recent elections underlined the actual weaknesses of our collective decision-making processes, either concerning the resulting lack of representativity (people getting elected but representing actually a minority of the population) or more globally the efficiency of the decisions taken. A significant gap exists in between on one hand the opinions of a networked population that are structured and evolve using social media, leading to a much more visible diversity and on the other hand the ones of representatives that are still structured by political parties. Such a situation leads to questioning the processes used to choose representatives and more globally to make collective decision-making with alternatives that are proposed more and more (liquid democracy for instance (Blum and Zuber, 2016). The article by Sueur et al. shed new light on the situation by proposing to examine further the solutions selected along time by the animal kingdom in order to make collective decision-making. Although they advocate that the decisions taken are not the same (decision for an animal group to move to another place) and do not involve the same cognitive abilities at the individual level, the existing processes could get adapted to human contexts. One of the most striking advantages of such bio-inspired approach is that animal collective decision-making processes are robust and enable to manage conflicting views, diversity of opinions and avoid forms of despotism that are not much present in animals, rather consensual decision-making being the norm. Another argument, probably less put forward by the authors is that such solutions may scale well with large networked populations as they exist for some animal species. Therefore it looks like we could have a kind of readymade library of processes for collective decision-making that are yet efficient to make timely decisions for different purposes with different population sizes and structures. Their argument is consolidated by the possibility of using AI technologies in order to enable to support the adaptation of such solutions. Without building explicitly the link, they identify that AI could be used in order to guarantee a fair process and to scale up the proposed solutions at the level of massive populations. This is probably the less convincing part of the proposal and it concerns the relation between human and AI. Even if the authors admit that the acceptance of AI solutions by part of the population is a key issue, as it concerns directly the legitimacy of the process and the compliance of the population with the resulting decision. They tend to minimize the gap to fill before having a fair AI with potential behavior that can be verified before using it with confidence to support a democratic process of decision-making. Nevertheless, the article brings forward good arguments, well formalized using relevant concepts for the use of bio-inspired solutions for collective decision-making. References Blum C, Zuber CI (2016) Liquid Democracy: Potentials, Problems, and Perspectives. Journal of Political Philosophy, 24, 162–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12065 Sueur C, Bousquet C, Espinosa R, Deneubourg J-L (2021) Improving human collective decision-making through animal and artificial intelligence. hal-03299087, ver. 3 recommended and peer-reviewed by Peer Community in Network Science. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03299087 | Improving human collective decision-making through animal and artificial intelligence | Cédric Sueur, Christophe Bousquet, Romain Espinosa and Jean-Louis Deneubourg | <p style="text-align: justify;">Whilst fundamental to human societies, collective decision-making such as voting systems can lead to non-efficient decisions, as past climate policies demonstrate. Current systems are harshly criticized for the way ... |  | Animal networks, Political networks | Frédéric Amblard | 2021-04-19 07:10:05 | View | |

05 Jul 2022

Linking parasitism to network centrality and the impact of sampling bias in its interpretationZhihong Xu, Andrew J. J. MacIntosh, Alba Castellano-Navarro, Emilio Macanás-Martínez, Takafumi Suzumura, Julie Duboscq https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.07.447302Centrality and parasite loads in sampled networksRecommended by Matthew Silk based on reviews by Krishna Balasubramaniam, Quinn Webber and 1 anonymous reviewerNetworks provide an ideal tool to link social behaviour and infection in animal societies (White et al. 2017). A major focus of previous research has been on the links between social centrality and infection (Briard & Ezenwa 2021). But what happens when conclusions are drawn from sampled networks in which some individuals are not observed, or when studies focus on some individuals at the expense of others (e.g. adults versus juveniles or females versus males)? Xu et al. (2022) examine how focusing on different samples of individuals in a network analysis relating centrality to parasite load in Japanese macaques Macaca fuscata influence the conclusions drawn. Xu et al. (2022) use faecal egg counts to estimate parasite loads of three environmentally transmitted parasites Oesophagostomum aculeatum, Strongyloides fuelleborni and Trichuris trichiura in a group of macaques on Koshima Island, Japan. After showing positive associations between parasite load and strength (the sum of an individual’s connections) and eigenvector centrality (accounting for second-order connections) in a 1-metre proximity network, the authors explore how this result is impacted by focusing on only adult females, only juveniles or random sub-samples of the population. Their results indicate that the positive association persists more strongly in the adult female networks albeit with reduced statistical power to detect it. It is largely absent in juveniles (either based on their centrality in the full network or centrality in the juvenile-only network). Random removal of individuals from the network led to a rapid reduction in the ability to detect the same positive association between centrality and parasite load due to a combination of changes in individual centrality in re-sampled networks and reduced statistical power. The timescale of network data collection and proximity networks studied are (likely) not fully relevant for the transmission of these parasites and social transmission of the parasites studied here is likely to be limited, there remain other reasons that we may expect correlations between sociality and infection (Ezenwa et al. 2016). Nevertheless, this is a useful contribution to the literature on sampling effects in animal networks, complementing existing work (Franks et al. 2010, Silk et al. 2015, Davis et al. 2018, Silk 2018). The results from considering different sub-samples of the group show the potential importance of carefully considering whether social network effects will be equivalently important for the whole population and which interactions will contribute either to promoting health or increasing the risk of infection. The results of random sub-sampling show how in small (within-group) networks such as these even small numbers of missing individuals could have substantial impacts on testing how traits are associated with the social network position of individuals. The findings set up some interesting questions about how best to develop effective sampling designs in single-group studies such as these, or in how best to extend these types of projects across multiple groups (see also Silk 2018). Testing the generality of these findings across taxa with different social systems and infection prevalences or loads will also be a valuable next step for behavioural disease ecology. References Briard L, Ezenwa VO. 2021. Parasitism and host social behaviour: a meta-analysis of insights derived from social network analysis. Anim. Behav. 172, 171-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.11.010 Davis GH, Crofoot MC, Farine DR. 2018. Estimating the robustness and uncertainty of animal social networks using different observational methods. Anim. Behav. 141, 29-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2018.04.012 Ezenwa VO, Ghai RR, McKay AF, Williams AE. 2016. Group living and pathogen infection revisited. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 12, 66-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.09.006 Franks DW, Ruxton GD, James R. 2010. Sampling animal association networks with the gambit of the group. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 64, 493-503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-009-0865-8 Silk MJ, Jackson AL, Croft DP, Colhoun K, Bearhop S. 2015. The consequences of unidentifiable individuals for the analysis of an animal social network. Anim. Behav. 104, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.03.005 Silk MJ. 2018. The next steps in the study of missing individuals in networks: a comment on Smith et al. (2017). Soc. Net. 52, 37-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2017.05.002 White LA, Forester JD, Craft ME. 2017. Using contact networks to explore mechanisms of parasite transmission in wildlife. Biol. Rev. 92, 389-409. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12236 Xu Z, MacIntosh AJJ, Castellano-Navarro A, Macanás-Martinez E, Suzumura T, Dubosq J. 2022. Linking parasitism to network centrality and the impact of sampling bias in its interpretation. bioRxiv 2021.06.07.447302, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.07.447302 | Linking parasitism to network centrality and the impact of sampling bias in its interpretation | Zhihong Xu, Andrew J. J. MacIntosh, Alba Castellano-Navarro, Emilio Macanás-Martínez, Takafumi Suzumura, Julie Duboscq | <p style="text-align: justify;">Group living is beneficial for individuals, but also comes with costs. One such cost is the increased possibility of pathogen transmission because increased numbers or frequencies of social contacts are often associ... |  | Animal networks, Biological Networks, Contact networks | Matthew Silk | 2021-06-20 16:29:07 | View | |

04 May 2022

Long term analysis of social structure: evidence of age-based consistent associations in male Alpine ibexAlice Brambilla, Achaz von Hardenberg, Claudia Canedoli, Francesca Brivio, Cedric Sueur, Christina Stanely https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.02.470954A social network of bucksRecommended by Gabriel Ramos-Fernández based on reviews by Brenda McCowan and Sandra Smith Aguilar based on reviews by Brenda McCowan and Sandra Smith Aguilar

How do social networks change over the long term? What features are more stable? Are there individuals that maintain their position? What factors determine this? These are the questions that Brambilla et al. (2022) successfully address in their manuscript, for a network of male Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) in the northwestern Italian Alps. While it is widely acknowledged that animal social networks are dynamic (Pinter-Wollman et al. 2014) not often can we see analyses of this temporal variation using data sets collected on the same individuals for long periods of time. Brambilla et al. (2022) collected such a data set on individually identified bucks from a wild-ranging population for ten years. Alpine ibex populations are sexually segregated except for the rutting period, which justifies focusing a social network analysis on each of the sexes separately. They also present a low degree of fission-fusion dynamics, forming cohesive groups or spreading over larger areas depending, presumably, on the resource heterogeneity. Taking advantage of the fact that temporary subgroups can be observed, Brambilla et al. (2022) measured the degree of association between individual bucks by the time they spent in the same subgroup. Building yearly networks with links thus defined, the authors were able to analyze the changes and stability of networks across the years. In all yearly networks, all bucks are connected in a single, giant component, which implies either that subgroups were sufficiently fluid in composition to include all possible pairs of individuals at least once, or that bucks formed temporarily large subgroups that included all of them, at least sometimes. This connectedness of the networks, as well as their high link density, prevailed over the whole study and can be said to characterize buck social networks. Other features, like the degree of centralization, differed between summer and spring networks, but in a consistent fashion across years, suggesting that the degree of resource heterogeneity (which is higher in the spring, when the snow melts only at low altitude) influences the association patterns between bucks. When analyzing the social network metrics at the node level, Brambilla et al. (2022) found a very clear effect of age, with individual degree and eigenvector centrality increasing and then decreasing as bucks aged. In fact, bucks showed mostly peripheral positions in the network of the year before their death. These results add to the accumulating evidence that age and social position are intricately linked (Sueur et al. 2021). The yearly networks also showed strong homophily by age, with bucks of similar age showing stronger bonds than those of different age, and an opposite effect of dominance rank, with bucks of similar rank showing weaker bonds than those of dissimilar rank. In addition to the obvious integration of these results to those of the female social networks, including the rutting period, it remains to be studied what mechanisms at the individual and behavioral levels could lie behind these patterns: are individuals of similar age also similar in their nutritional requirements? Are they more familiar with each other because of spending time together since young? Are older individuals unable to invest in maintaining social relationships and therefore displaced from more central positions in the network? Are similarly ranked individuals more likely to enter into conflict and therefore avoid one another? Does personality influence patterns, beyond dominance rank or age? These are open questions that result from a solid study, which counts as its strengths the longitudinal data set, rigorous methods for analyzing networks at the global and node levels and for statistically testing differences and similarities between networks at different points in time and a nicely written literature review with a broad taxonomic scope. References Brambilla A, Hardenberg A von, Canedoli C, Brivio F, Sueur C, Stanley CR (2022) Long term analysis of social structure: evidence of age-based consistent associations in male Alpine ibex. bioRxiv, 2021.12.02.470954, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.02.470954 Pinter-Wollman N, Hobson EA, Smith JE, Edelman AJ, Shizuka D, de Silva S, Waters JS, Prager SD, Sasaki T, Wittemyer G, Fewell J, McDonald DB (2014) The dynamics of animal social networks: analytical, conceptual, and theoretical advances. Behavioral Ecology, 25, 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/art047 Sueur C, Quque M, Naud A, Bergouignan A, Criscuolo F (2021) Social capital: an independent dimension of healthy ageing. HAL, hal-03299528, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03299528 | Long term analysis of social structure: evidence of age-based consistent associations in male Alpine ibex | Alice Brambilla, Achaz von Hardenberg, Claudia Canedoli, Francesca Brivio, Cedric Sueur, Christina Stanely | <p style="text-align: justify;">Despite its recognized importance for understanding the evolution of animal sociality as well as for conservation, long-term analysis of social networks of animal populations is still relatively uncommon. We investi... | Animal networks | Gabriel Ramos-Fernández | 2021-12-04 10:19:50 | View | ||

19 Oct 2021

Social capital: an independent dimension of healthy ageingCédric Sueur, Martin Quque, Alexandre Naud, Audrey Bergouignan, François Criscuolo https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03299528How to age happily in a healthy networkRecommended by Gabriel Ramos-Fernández based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

What is the relationship between social capital and healthy ageing? This is the simple yet ambitious question that Sueur et al. (2021) tackle in their review. The relationship between social capital (understood as the resources an individual has access to by virtue of belonging to a social group) and health has been the subject of discussion at least since the work of Émile Durkheim (1897) who emphasized the social roots of individual health problems, such as stress and its extreme form, reflected in suicidal tendencies. The discipline of medical sociology studies the social determinants of health, partly by focusing on those components of the social capital of individuals that directly influence their health (Cockerham 2017). Using a comparative approach and focusing more on senescence than chronological ageing, Sueur et al. (2021) provide ample evidence that social capital has a positive relationship with fitness in many animal species, while stressing the plastic nature of senescence and therefore, pointing at the possibility that one way of improving health over an individual’s life span could be to improve its social capital. This dynamic view of the relationship between social capital and health, as a determinant of healthy ageing as a process, is one of the main conceptual contributions of this work. Another important contribution is the multi-level framework used by the authors in their review. Taking into account the cellular, endocrine, behavioral, individual and social network levels into the same conceptual scheme is a welcome attempt in view of the traditional reductionistic approaches taken in biomedicine. Another strength of the paper is the use of clearly explained boxes to tackle complicated and long-debated terms like social capital or display a full glossary with all the important terms introduced in the paper. The authors point at the potential mechanisms by which social capital could affect senescence. Here, it is worth pointing out the contemporary context in which one mechanism identified by the authors, takes place in human communities. Since the work of Seyle (1970) it is well known that stress hormones produce a kind of premature ageing process due to a continued stress response. Clearly, socially determined stressful conditions such as racism in modern society, can lead to the activation of coping mechanisms that may be related to premature ageing (e.g. Geronimus et al. 2006). A word of caution is particularly relevant: social capital can also have negative effects on health, the most obvious in the context of a pandemic like COVID-19’s being a higher risk of contagion from social exposure. It remains to be seen whether the way in which the human population has adapted as individuals and societies to this risk has necessarily implied a sharp, and probably costly, decrease in social capital. Overall, this paper should be a good introduction to the intricate relationships between healthy ageing and social capital, hopefully inspiring further research using both animals and humans to understand the social component of ageing. References Cockerham WC (2017) Medical Sociology. Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315618692 Durkheim É (1951) Suicide: a study in sociology. Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois. Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J (2006) “Weathering” and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores Among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 826–833. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 Selye H (1970) Stress and Aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 18, 669–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1970.tb02813.x Sueur C, Quque M, Naud A, Bergouignan A, Criscuolo F (2021) Social capital: an independent dimension of healthy ageing. HAL, hal-03299528, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03299528 | Social capital: an independent dimension of healthy ageing | Cédric Sueur, Martin Quque, Alexandre Naud, Audrey Bergouignan, François Criscuolo | <p style="text-align: justify;">Resources that are embedded in social relationships, such as shared knowledge, access to food, services, social support or cooperation, are all examples of social capital. Social capital is recognised as an importan... |  | Adaptive networks, Animal networks, Contact networks, Network measures, Social networks | Gabriel Ramos-Fernández | 2021-05-24 17:20:14 | View | |

20 Sep 2023

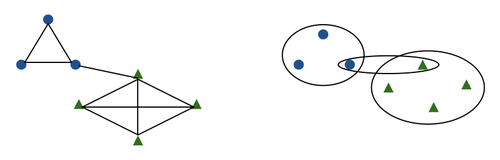

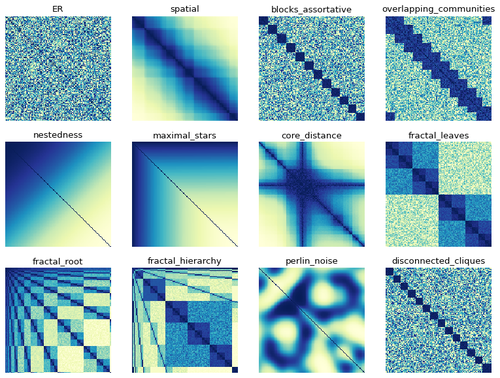

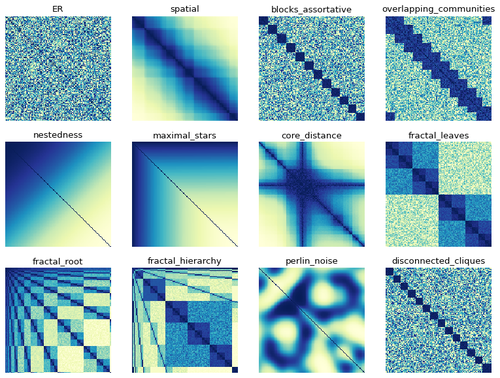

Structify-Net: Random Graph generation with controlled size and customized structureRemy Cazabet, Salvatore Citraro, Giulio Rossetti https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.05274A model petting zoo for interacting with network structureRecommended by Leto Peel based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIf you work, study or play in network science then chances are you have generated a network. Whether or not you have a real-world system to analyse, synthetic networks play an important role in network science. Generating networks of a chosen size can provide a null model for a statistical test, a test bed for new algorithms or the basis for studying the interplay between structure and dynamics in complex systems. Consequently network science literature contains a wide array of network models: some designed as processes to replicate observed properties and others for the purposes of statistical inference. However, these models have different parameters and constraints associated with their generative models, may or may not have the ability to control for random noise and do not always have readily available software implementations, thus making them unavailable to network science practitioners. The article of Cazabet et al. (2023) introduces a software "zoo, " called Structify-Net, that contains a range of models that the authors have captured from the wild. The authors have focused on developing a framework that enables the generation networks of a chosen size, according to number of nodes and edges, and provides the means to control for randomness, by interpolating between the specified structure and a random graph. The article also discusses an interesting use case to examine the interplay between network structure and node attributes, which might compliment methods based on permutation tests (Bianconi et al. 2009, Ehrhardt and Wolfe 2019). Structify-Net presents some interesting future opportunities. For instance, the independence that Structify-Net imposes on edge ranking (defined by the model) and the expected number of edges (defined by the user) might offer a route towards exploring network growth or evolution. Like any zoo Structify-Net is not complete in that there are many more exotic "species" that the authors, or perhaps others in the network science community, may later collect. Collecting more model implementations to align with reviews of network models (Goldenberg et al. 2010) together with methods of statistical inference has the potential to lay the foundations for the ever important bridge between theory and practice in network science (Peel et al. 2022). References Bianconi, Ginestra, Paolo Pin, and Matteo Marsili (2009) Assessing the Relevance of Node Features for Network Structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 28: 11433–38. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811511106 Cazabet, Remy, Salvatore Citraro, and Giulio Rossetti (2023) Structify-Net: Random Graph Generation with Controlled Size and Customized Structure. arXiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Network Science. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.05274 Ehrhardt, Beate, and Patrick J. Wolfe (2019) Network Modularity in the Presence of Covariates’. SIAM Review 61, 2: 261–76. https://doi.org/10.1137/17M1111528 Goldenberg, Anna, Alice X. Zheng, Stephen E. Fienberg, and Edoardo M. Airoldi (2010) A Survey of Statistical Network Models. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2, 2: 129–233. https://doi.org/10.1561/2200000005 Peel, Leto, Tiago P. Peixoto, and Manlio De Domenico (2022) Statistical Inference Links Data and Theory in Network Science. Nature Communications 13, 1: 6794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34267-9 | Structify-Net: Random Graph generation with controlled size and customized structure | Remy Cazabet, Salvatore Citraro, Giulio Rossetti | <p>Network structure is often considered one of the most important features of a network, and various models exist to generate graphs having one of the most studied types of structures, such as blocks/communities or spatial structures. In this art... |  | Algorithms for Network Analysis, Clustering in networks, Community structure in networks, Geometry and topology of networks or graphs, Graph models, Network models, Random graphs, Spatial networks, Structural network properties | Leto Peel | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2023-06-09 10:41:32 | View |

22 Feb 2024

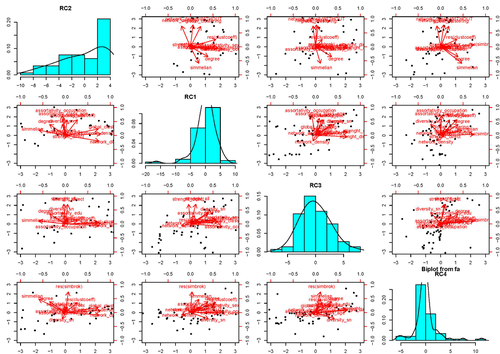

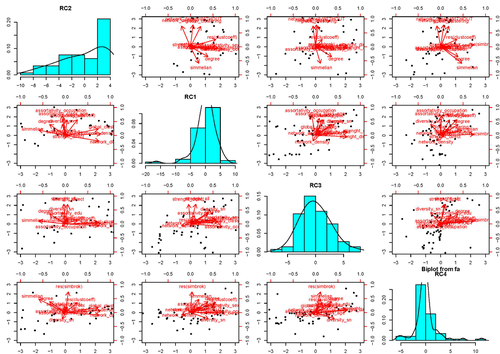

The Complexity of Social Networks in Healthy Aging: Novel Metrics and Their Associations with Psychological Well-BeingSueur Cédric, Giovanna Fancello, Alexandre Naud, Yan Kestens, Basile Chaix https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/j9uz8An application of PCA to social networks and healthy ageingRecommended by Steve Lawford based on reviews by Christophe Prieur, Paul Rochet and 1 anonymous reviewerSueur et al. (2024) investigate the influence of an individual’s social network structure on various aspects of healthy ageing, including depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and overall well-being. The primary dataset comprises 73 adults aged 60 and above, residing in the Paris region from 2019 to 2020, who completed a VERITAS socioeconomic/demographic questionnaire; and is augmented with official data on the characteristics of residential neighbourhoods. The authors apply principal component analysis (PCA) to network structure metrics including degree centrality, density, and global clustering, and identify four dimensions that they argue have social significance: homophily, social integration, social support, and perceived accessibility to local services. Unexpectedly, the authors’ statistical analysis reveals that none of the PCA dimensions are linked to healthy ageing. Although network-based PCA dimensions have been used as explanatory variables in other settings, this paper may be the first to apply the technique to healthy ageing. The main result stands in contrast to related literature which indicates that positive social relationships (engagement, sense of community) are related to more favourable mortality and disease outcomes and that these effects persist as people become older. The paper is a useful contribution to an issue that has considerable public health policy importance. It will motivate further research to understand the negative main result, including potential information loss from PCA, issues of small sample bias and identification (relatively few of the respondents were depressed or anxious), specificity of the survey to the Paris region, and more advanced econometric modelling to better understand causal relationships (rather than correlations) between social networks and well-being in older people. Reference C. Sueur, G. Fancello, A. Naud, Y. Kestens, and B. Chaix (2024) The complexity of social | The Complexity of Social Networks in Healthy Aging: Novel Metrics and Their Associations with Psychological Well-Being | Sueur Cédric, Giovanna Fancello, Alexandre Naud, Yan Kestens, Basile Chaix | <p>Social networks play a crucial role in promoting healthy aging, yet the intricate mechanisms connecting social capital to health present a complex challenge. Additionally, the majority of social network analysis studies focusing on older adults... |  | Contact networks, Network measures, Personal network analysis, Social networks | Steve Lawford | 2023-03-23 14:41:55 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Eleni Akrida

Corinne Bonnet

Alecia Carter

Michel Grossetti

Norbert Hounkonnou

Pablo Jensen

Matthieu Latapy

Brenda McCowan

Elisa Omodei

Cédric Sueur